It’s in the Telling

A Memoir by Beth Schorr Jaffe

He hasn’t seen me in a few months. So glad, he says, I have come in, finally. The Korean clerk behind the dry cleaner’s counter thinks he is in for a happy chat today when I come in to pick up my husband’s shirts. I usually banter about an idiotic thing I’ve done, like when I crushed my eyeglasses while backing out of the garage.

I tell him immediately, “My father died. I’ve been staying home a lot.”

“Oh, so sorry, Mrs. Jaffe.” He lowers his head and frowns.

“You remember? My father was a dry cleaner,” I remind him. The winter rushes in before the store door drags itself shut; so intimate are we — me, the clerk, and my dad. He hurries to gather my items, as if I am going to be late for a funeral. I collect my husband’s shirts and thank him with a polite smile. I make my way to the beauty supply center a few doors down in the highway mall. I don’t really want anything, but I feel like walking the peaceful, self-centered aisles. Women walk slowly, thoughtfully, in the beauty store. I stop in front of the Maybelline products and numbly peruse the multitude of mascaras on the wall racks. X times longer. XX, XXX times. An adorable, petite teenager wearing a smock comes over and asks me if I need help. Oh for sure, I tell her. So many to choose from. I recite I need black mascara that is very, very waterproof. Like a chess game, I have thought out the conversation three moves ahead and lead her to checkmate.

“This is a very, very waterproof one,” she recites back to me.

“I need a very, very waterproof one because I cry all the time.”

“Oh?” she says. Her face is blank except for the ever so slightly peaked eyebrows, not as much questioning as frightened. She is very young and I am so middle-aged. I am wearing a long, gray coat, and the cuffs of my orange sweatshirt, a little frayed, extend past my wrists, so of course, I imagine she thinks I must be a homeless person.

“I cry for a reason, of course.” I giggle a teeny giggle for her comfort. “I cry because I just lost my father and I am still mourning. I’m sorry if I made you uncomfortable.” I touch her elbow.

She squirms a step back. “That’s okay. I’m sorry. Just happen?”

“No. Three months ago.”

“Oh.” Her eyebrows re-emerge. Now I know she has lost any sympathy she may have had. Like others who have not yet lost, she thinks I should have stopped crying by now.

“Three months is not a long time really. I mean, I have a husband whom I love, but my father was the love of my life.” She is too young, too wild to understand. It is time to choose mascara and move on. “You think the very, very waterproof, XXX is the one I should buy?”

She concurs and we proceed to the checkout.

I have told two more people. The makeup girl will forget, but the dry cleaner will tell his family I am sure. Perhaps they will say some kind of Korean prayer for us.

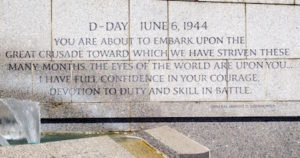

Perhaps every time we come in they will remember that he lived and died. I become upset that I didn’t take out his picture. I carry the photo of him when he was in the Army, dressed as a bugler playing the trumpet. Then if someone asks, I can tell more stories about him. And they can remember him as a musician and a war hero. A picture tells a thousand words, but I add a few, and make sure they understand how much is actually missing. When I go back to the cleaner I will show him the picture. I begin thinking of dirty clothes I can start collecting to bring. Disappointed my husband had not spread the word to the dry cleaner, I am more than curious about

why he would let that fact go without saying.

Is it only the first thing out of my mouth? I concede that it is not newsworthy, in the scheme of the universe. But still I am paralyzed, gripped with the knowledge that even my husband does not understand, has not seen it as worthy of telling: The one man who thought so much of me has died, and with his death, there is also no one left, no clues, no evidence, that in the entire world, a fantastical man had idolized this one particular fantastical girl. Where does that leave me?

My last stop on the way home is, unfortunately, the grocery. There is no more lonely and isolating place. Everyone hates where they are, rushing to get in and out. I start to become anxious about the excursion, not only the task at hand, buying sustenance, but also the barren tunnels, the women with their children in carts, wiggling around you as if on a crowded highway trying not to crash. Just get the hell out of here alive and get home.

I eat a lot of carbs these days. Bread of choice: sourdough. It has to be sliced. The bread counter is empty. I hand the woman at the bakery my loaf. I breathe deep. I try very hard to control myself. I cannot tell her. It is inappropriate. She does not care. She does not know me. But when she hands me the bread in the plastic bag my eyes start to water.

“You look so sad today, sweetie,” she says. “Everything okay?”

“It’s been a rough couple of weeks,” I say. “I just lost my father. He loved sourdough.”

“Oh I’m so sorry.” And then she comes around to me, from behind her glass pastry barrier. “I lost my father 10 years ago and I miss him every day,” she confides in me.

“Really. I’m sorry I brought it up.”

I go home and phone my mother. She is alone in their apartment, grieving the loss of her husband of 65 years.

“Mom, what do you say I come over and we put together that photo album of Dad’s Army pictures?”

“I already have the boxes of all his war pictures waiting on the table.”

Back in the car I decide I won’t let her know about his bugler picture in my wallet.

Beth Jaffe lives in Sag Harbor and is the author of a novel, “Stars of David.” She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in English literature and creative writing from Brooklyn College, and has had short stories, poems, and essays published in numerous publications.